Scott Williams Knows Analytics

Didn't matter if [Allen Iverson] was shooting 38% from the field, he only cared about getting 30 shots. Well, hell, you give me fricken 25 shots Ima score 20 points a game too.

I heard Scott Williams say these words on the Ben Guest Podcast while driving home from dropping my son at daycare. Part of me wanted to cheer like a sports fan. Scott Williams was on fire with his sports takes. And, indeed, listen to both parts of his interviews with Ben if you haven’t (Part 1 Here). Another part me of felt like Robin Williams in Good Will Hunting: “Son of ****, he stole my line.”

While Ben was interviewing Scott, I was working on a fun project. I looked for players in NBA history that had scored 20 points per game and were leaderboard eligible (played 70% of their team games). Of players that had two or more seasons, there was a 91% chance they’d been named to an All-Star game in their career. I should note, some players, such as C.J. McCollum and Collin Sexton, are on this list and seem likely candidates to become All-Stars eventually. For players with multiple seasons at 25 points per game? 98% they’d been an All-Star. Only Purvis Short fits that bill without an All-Star game on his resume. And an apparent reason for that was injury. After back-to-back seasons at 25+ PPG, Short was injured in the 1987 NBA season and never regained his form.

I came up with some terms for this - “The ‘Real’ Usage Curve” and “The 20-Point Wall”. I have shown it below in fun graphical form.

A brief explanation of a few terms:

True Shooting Percentage is [Points Scored]/(2 * ([Field Goals Attempted] + 0.44 * [Free Throws Attempted]). The logic is what percentage of shot possessions end up in two points. Scoring 20 points on ten shots would be a True Shooting Percentage of 100%. Of course, three-pointers add a hiccup, so a player’s max True Shooting Percentage is 150%!

True Shots As noted above, the goal of True Shooting Percentage is to estimate points per shot. This helps for three-points and two-pointers. Free Throws add a wrinkle as a player gets between one and three attempts when they go to a line, and only one of those ends the possession. Dean Oliver estimated 0.44 to adjust for and-ones and three-point free-throw occurrences.

A topic we’ll revisit is Dean Oliver’s “Skill Curves.”, which, to put it politely, is one of the worst analytics ideas ever introduced to the basketball nomenclature. The idea Dean posited was as a player’s usage went up (how many possessions they spent), their efficiency would have to go down. There are many flaws with this line of thinking, and by Dean’s own volition, the data to support it is sparse. However, it does line up the curve above. If a player aims to score 20 points per game, they can achieve this with worse shots, provided their shots go up. Scott Williams' “38% on 30 shots” was almost remarkably spot-on. And it showed something Allen Iverson knew. Using another old sports movie quote, this time from Crash Davis in Bull Durham.

Your shower shoes have fungus on them. You'll never make it to the bigs with fungus on your shower shoes. Think classy, you'll be classy. If you win 20 in the show, you can let the fungus grow back and the press'll think you're colorful. Until you win 20 in the show, however, it means you are a slob.

In baseball, twenty wins for a pitcher is a mythical number signifying greatness. And in basketball, twenty points per game is the same. And the players know this. The logic of the “Skill Curve” doesn’t line up with productive offenses in the NBA. It does line up for players intentionally trying to get paid. Let’s talk about three of them.

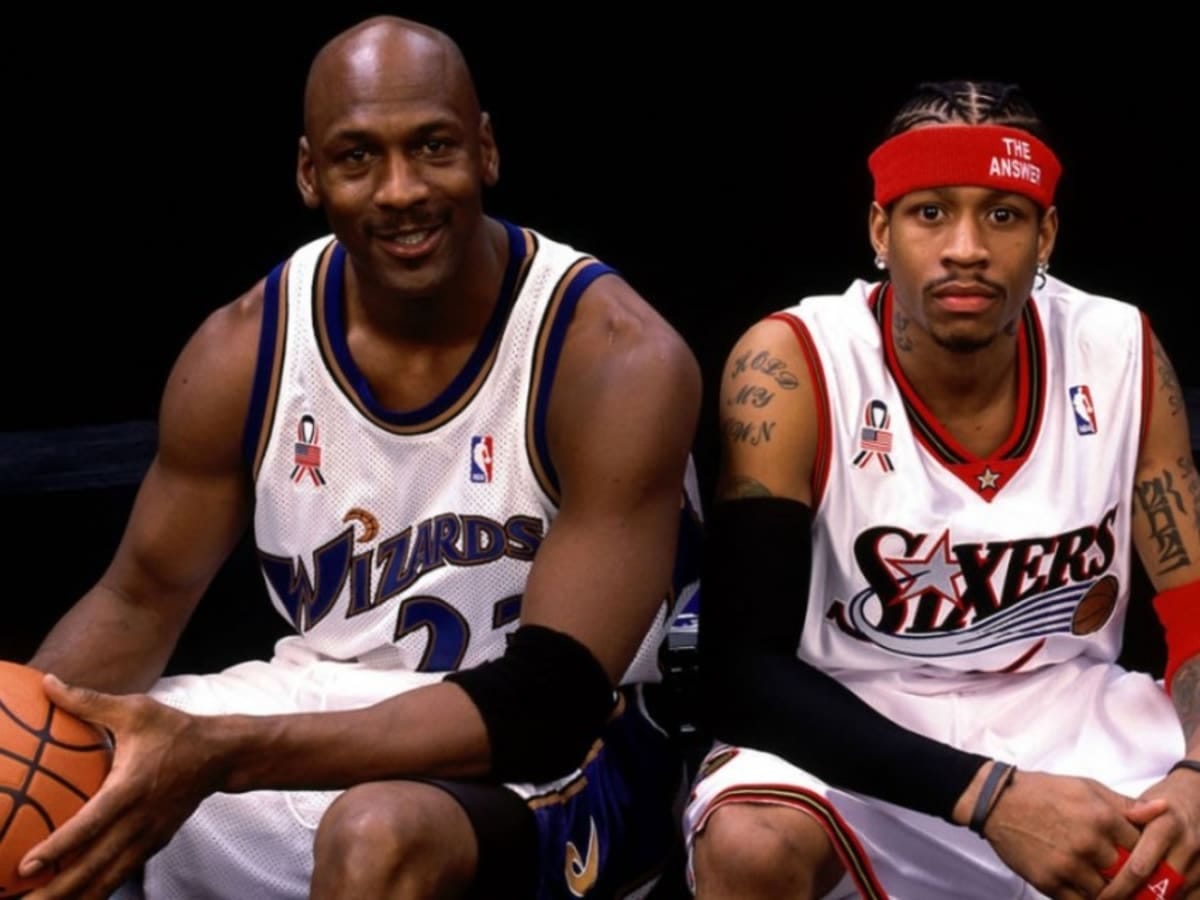

Scott and Ben discussed Allen Iverson. Ben noted the sad end to Allen Iverson’s career. After All-Star stints in Philadelphia and Denver, AI ended up in Detroit. He increased his shots per game, but he was only able to score 17.4 points per game. At this point, he was in his late thirties and dealing with back injuries and off the court issues. Rather than take a reserve role, Iverson went to Memphis, where he could only average 12.3 points per game over three games. A big part of this was minutes. His scoring efficiency went up, but he couldn’t get enough shots in a game to hit 20. He found his way back to Philadelphia, who did give him minutes. But he was only able to average 14 points per game. And with that, Allen Iverson’s time over the 20-Point Wall was done. And so was his time in the NBA.

It’s possible he could have kept going as a reserve as Carmelo Anthony has done recently. But both Melo and Iverson saw their value go from over $20 million per year to $1-$2 million when they fell below the 20-Point Wall. Let’s bring up the GOAT in terms of the 20-Point Wall.

Kobe Bryant was a player that understood this. Many of us watched as he went from an MVP-calibre player to a chucker. Kobe Bryant is the all-time leader in missed shots, a record unlikely to be matched. But Kobe Bryant was the highest-paid player as a 37-year-old in his retirement season. He never fell below the 20-Point Wall in any healthy season after he was 21. In his last season, he kept on chucking, only limited by his time on the court. Many players regard Kobe Bryant as the greatest of all time. And I often laugh at that in terms of production. But it makes sense many players would want to emulate him. As soon as he left his rookie contract, Kobe stayed above the 20-Point Wall and ended one of the highest-paid players ever. An obvious goal for any NBA player!

Wall and the 20-Point Wall

John Wall is a former number one pick. Sadly he’s dealt with injuries the past four seasons. But he is the epitome of the 20-Point Wall, and I’d be remiss not to use him in this article given the name. Last season John Wall was included in a trade for Russell Westbrook. The difference in performance was staggering. But some are happy about John Wall, and there’s a straightforward reason, he’s at 20.2 points per game. And if he can keep it up? He might have one more big contract in him. This is especially important as this is the last year of his contract. So expect John Wall to aim for twenty points a game. John Wall is gambling with house money. His next season is a player option for $40 million. If he keeps his scoring above 20 points per game, he can take an expensive extension. If not, he can take the guaranteed cash.

When we watched Allen Iverson, Melo, and Kobe Bryant insist on shooting and insist on taking the starting roles, it was easy to be upset. They were terrible teammates. They weren’t winning. But the goal of NBA players is to get paid. Even ordained superteams can lose out on titles due to bad luck. The NBA front offices and media have erected an undeniable line in the sand. Get 20 points per game, and you’re a star. You’ll get the awards and the money if you can get over that wall. And players will do anything necessary to do it. They’ll chuck up shots. They’ll demand to be starters when they’d be better off the bench. People watching NBA “stars” like John Wall next season would do well to keep in mind. Of course, Scott Williams noticed this decades ago, and teams are still falling for it. So I’m not holding my breath.